In Bangladesh' textile factories 85 percent of the workforce are women. They are now fighting for a better salary and improved working conditions. Photo: CCBY ILO Asia-Pacific

Textile workers fight for better rights

The conditions for employees in the clothing industry in Bangladesh are slowly improving due to, among other factors, strong-minded female factory workers who fight for better rights in the tough and ungrateful textile working industry.

Share

Other categories

Region: Asia

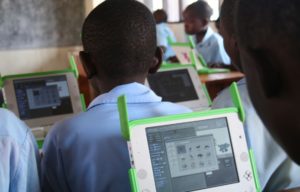

Many large fashion companies are producing their clothes in Bangladesh, where exports from the textile industry have grown from $ 9 billion to $ 29 billion in just ten years. Eighty-five percent of workers in the country’s 4825 textile factories are women, and although there has been an economic recovery, the seamstresses have not benefited from it. A minimum wage of just 63 US dollars a month, poor job security, and 12-hour working days is the reality for many of the 4.5 million female factory workers.

But many seamstresses have had enough. The women want fair working conditions but attaining them is not easy. This exact struggle has been adapted for the big screen and turned into a film that recently premiered in cinemas around the world, including Denmark.

Eleven-year-old fled from home to start working

The film Made in Bangladesh is based on the real story of the seamstress Daliya Akhter. She ran away from home at age eleven in order to avoid an arranged marriage.

“My parents wanted me to marry, but I didn’t want to. I ran away and ended up in the capital of Dhaka. It often happens that girls flee from their homes to avoid getting married,” she says in an interview in relation to the film.

In Dhaka, Akhter got a job in a clothing factory – a job of grave importance since many unemployed women in Bangladesh are at greater risk of ending up in an unwanted marriage or as prostitutes. But working conditions gradually worsened with poor salary, loss of rights, and insecure working facilities. After a seamstress was killed in a factory accident, Akhter had had enough. She set out to learn about labour law and after a long, tough fight she started a union with the other seamstresses – a union she ended up leading.

“I wanted to not only fight for myself but for the entire community and help people towards a better life,” she says.

Women fight for their rights

According to the director of Made in Bangladesh, Rubaiyat Hossain, it was important not to portray the women as victims, but rather as individuals who fought against an unfair system.

“There are so many extraordinary women like Daliya in Bangladesh, which is why I wanted to make this film. We often see these women as victims and as some we should feel sorry for, but there are so many women who make positive changes in their communities,” Hossain says, based on her own personal experience working with women’s rights in Bangladesh before becoming a film director.

And Akther’s story does not stand alone. More and more seamstresses want a change and join unions, and because of that, the number of unions has doubled since 2013.

Occupational safety has improved

The safety conditions in Bangladesh’s factories have also improved over the last ten years. Several large Western companies, NGO’s, and international and local unions have joined forces to secure better working conditions in the textile industry with the so-called ‘Accord Agreement’.

The agreement has, among other things, tightened the requirements for fire safety, since several clothing factories have been subjected to severe fire accidents, such as the fire in the Tazreen Fashions factory in 2012 which caused 112 deaths.

“The Accord Agreement has done a great deal. Lots of factories have been closed, including the factory where Daliya worked. It was closed because there were no sprinklers and the building was in such poor condition that they could not be installed,” Hossain says.

The Accord Agreement was put into action after the disastrous Rana Plaza accident in 2013, where 1134 workers died when a textile factory building collapsed.

“Following the Rana Plaza incident and subsequent investigations into the safety of the textile industry, 2000 factories were closed,” Hossain says.

Don’t boycott Bangladesh

But even though more and more women are fighting and organising in unions, there is still a long way to go. Just 3.8 percent of the workers are members of a union since many are afraid of being fired if they sign up for one. And when factory owners are further pressured by their employees’ claims for better conditions, it could end up with owners moving the production out of Bangladesh to somewhere with less working rights.

“It is like a chain reaction. After Daliya became a union leader and secured a lot of rights to her fellow workers, their factory closed soon after. And where are the workers then going?” Hossain says.

For consumers in the West, the solution is not to stop buying clothes from Bangladesh, Akhter explains. It will just push the cheap production somewhere else with worse conditions. There is a need for legislation and international organisations that can help push for a better direction.

“We need to work together to solve this problem – also across borders,” Akhter says.