Photo: UN Photo

In UN’s Best of All Worlds

What kind of world do you want? This question is posed to all citizens by the UN in the biggest survey in history.

Share

The analysis was published in Jyllands-Posten 24 June 2014

Other categories

‘I want this to be the most inclusive process about global development that the world has ever seen’. These are the ambitious words of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-Moon, and refer to the extensive work and political tussles ahead of next year’s UN summit, when countries must define the new global development agenda that will replace the so-called Millennium Development Goals.

Back in the year 2000, the largest gathering of world leaders in human history convened in their suits, dresses and national costumes in an air-conditioned conference room at the UN headquarters in New York. Here they wrote the document that became the foundation of those eight goals the world was asked to strive for in the coming 15 years in order to eradicate poverty. Like much else coming from the UN, the eight Millennium Development Goals were criticised for being technocratic and bureaucratic. However, roughly 500 days before the deadline, there is no doubt that the goals have had measurable and life-changing effects on billions of people: since 1990, half of the world’s extremely poor people have been lifted out of poverty, 2.1 billion people have gained access to clean water, the AIDS epidemic and malaria have been curbed, 90% of children in developing countries start school and just as many girls as boys. Still the world faces massive challenges: everything indicates that several of the goals will not be achieved. Meanwhile, the population curve is skyrocketing and the same goes for extreme natural disasters.

When the new goals for the next 15 years have been decided on next year in the United Nations, with Denmark and Papua New Guinea at the helm, no less than the planet’s future is at stake and that of all its inhabitants. Much suggests that this time the goals will involve all the nations of the world – also the richest. The overriding goal this time is to eradicate poverty, once and for all. It may sound unrealistic, but globally acclaimed extrapolations from the World Bank and other sources show that this is actually not an unrealistic scenario within our generation.

Hence lobbyism is already on the boil in conference centres around the world. The green NGO’s want climate and natural resources to top the agenda, while those who speak for children and young people want the world’s youngest represented in the shared set of global goals.

To meet Ban Ki-Moon’s vision of an open and inclusive process, the UN have launched nothing less than the world’s largest survey called My World. Here, this otherwise so introvert and bureaucratic organ asks ordinary people in all countries: ‘What kind of world do you want?’. The UN has done the preliminary work by choosing sixteen issues from which you must pick six that are of greatest importance for you and your family.

Perhaps the most important thing for you is to be able to send your children to a good school, or maybe you would choose better job opportunities. The sixteen issues have been carefully picked on the basis of the existing Millennium Development Goals, comprehensive research, broad surveys in selected countries (in Africa for example) and the existing political discussion about world development.

2,230,929 people from all the countries in the world have already sent their votes to the UN. Worldwide, a good education is the undisputed top priority. Better healthcare and an honest and responsive government hold second and third spots. Action taken on climate change scores the fewest points when looking at the world’s overall response. When delving into the Danish results, a completely different situation appears. Here, climate comes in third. Results from the survey, which can be accessed in real time at www.myworld2015.org, also show a unique insight into agendas and circumstances in each country worldwide. While it seems that a combination of comprehensive climate campaigns and local torrential rain storms have made an impact in Denmark, the Ukrainians, both numerously and not too surprisingly, want an honest and responsive government.

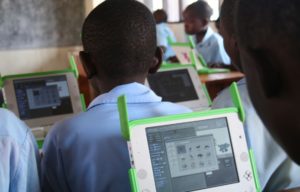

The UN’s goal is to start a global conversation involving the seamstress in Mumbai, the farmer in Mozambique, the high school teacher in Denmark and the UN representatives. The electronic survey has so far been translated into seventeen different languages, including Danish. But since the success of the survey depends on a wide range of age, social class and nationality, half of the votes have been collected through an offline strategy that in magnitude resembles the massive mobilising of volunteers who canvased during Obama’s election campaign. People from more than 900 organisations have walked and biked with ballot papers to remote villages in poor areas without the internet, and have asked everybody what kind of world they wish for. Girl Scouts representing the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts are among those who have had the greatest success in engaging people worldwide. For instance, in Kenya, girls in scout uniforms got Kenyan people to vote using a free text messaging system, so people could state their views by sending a text message to 21222. So far, the country where most citizens have made their voice heard as Sri Lanka, and the Sinhala and Tamil contributions represent 23.1% of all global voices in the MY World Survey to date.

This global referendum would seem to be a masterstroke by the UN office in New York. After being criticised for many years for top-down management, the UN now heralds an ultra-modern and democratic way of involving people in something as abstract as a summit conference about development goals. The global organisation assures us that the votes will be included as an important contribution to the debate, when politicians from all nations have to agree on how we can make the planet a better place moving on towards 2030. In September next year, individual countries will not only have a unique knowledge of what their population considers important in terms of living a good life, but the enormous compilation of data will also function as that extra human pressure the experts will need when the world leaders convene in New York. Unfortunately, history is full of examples of shattered summit dreams – the unsuccessful climate summit in Copenhagen has an unflattering ranking on that list. But this time it is going to be more difficult for the states to escape the governments. The whole world has been asked: from national consultations in each country, to experts and professionals, and right down to the man on the street in all the world’s 194 countries. Hence, for the first time ever, it looks like the United Nations is in a position to be one step ahead of the usual criticism that seems to be a permanent and time-consuming part of processes under its auspices. Hopefully, this will mean that the new global development goals will ensure that the world is a place where everybody has been lifted out of extreme poverty before 2030.