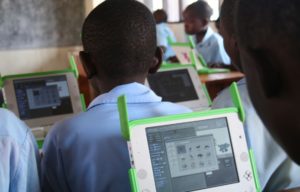

Boys in Afghanistan. Photo credit: UNDP CCBY

More vaccine against the ’toilet death’

Big investments in vaccine are set to break a vicious circle in the global struggle against the deadly bacterial disease cholera, which is a scourge to especially poor people and refugees.

Share

Deadly diarrhea

Extreme and deadly diarrhea. That is the possible consequence if you get infected by cholera.

The bacteria are transmitted by unclean water, and the first symptoms can appear within hours after contact with the water.

Without treatment, the disease can kill within hours, but with proper care, the chances of survival are good.

Treatment usually consists in drinking plenty of clean water with sugar and rehydration salts.

Every year, up to 4.3 million people are infected by cholera, and up to 142.000 die from the disease.

Other categories

Sudan and Haiti were not able to buy vaccine last year, when they asked the World Health Organisation (WHO) for supplies to prevent cholera outbreaks. There was simply not enough vaccine on the global market. But this situation is now set to change, since WHO in 2013 began to establish a global stockpile for cholera vaccine. This stockpile has so far meant that the distribution and use of vaccine against cholera is now at the highest level in 15 years.

Millions of doses

Meanwhile, the WHO continues to buy up large quantities of vaccine. This is done both to supply the global stockpile and to break the vicious cycle where high prices means small demand for the vaccine, which again leads to small production, which in turn means high prices. By procuring big volumes of vaccine, the WHO creates demand, which in turn leads to higher production and thus lower prices. This will make the vaccine more available and affordable to the countries that need it most.

Recently, the WHO has approved a new supplier, bringing the number up to three. This is expected to double the amount of vaccine available on the global market in 2016, with opportunities for further increases.

Oral cholera vaccine has been used since 1997, and requires one or two doses to provide two to five years of partial protection, depending on the type of vaccine. The supplies from the global stockpile has so far been used in 21 situations, to either fight an outbreak of cholera or to prevent outbreaks in locations where there is an increased risk of infection. For example during humanitarian crises in Haiti and Iraq, where many people were gathered without adequate access to clean drinking water and proper sanitation.

Clean water is the best vaccine

“The good thing about cholera is that it’s one of the world’s easiest diseases to prevent – all it takes is having enough clean water available”, says Peter Kjær Mackie Jensen, associate professor and leader of the Department of Global Health at Copenhagen University.

“Vaccines can be a part of the solution, especially in places like refugee camps, where huge amounts of people are packed closely together, maybe for years. But vaccines will never eradicate cholera by themselves, because at the end of the day, it’s a disease linked to poverty. So to get rid of cholera for good, we need to get rid of world poverty.”

Worldwide, 2.6 billion people have gained access to an improved water source since 1990, while the proportion of the urban population living in slums has decreased from 46 percent to 30 percent, according to statistics from the United Nations.