Photo: Amnesty International

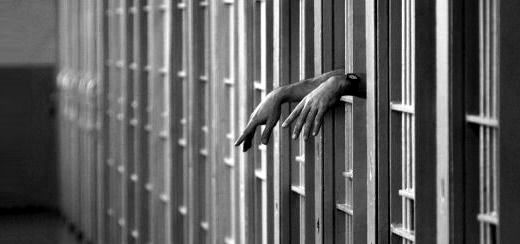

End of The Death Penalty

Countries that execute their citizens are increasingly isolated on the international scene. EU and the business community have brought the world closer to an abolition of the death penalty.

Share

The article was published in Jyllands-Posten 16 October 2013.

Lars Normann Jørgensen is the Secretary General of Amnesty International in Denmark, which is a part of World’s Best News.

Other categories

Region: Global

Theme: Civil Rights, Human Rights

Last year, the last prisoner was removed from death row in the West African country of Sierra Leone. The condemned prisoner had spent more than eight years on death row, but had his sentence converted overturned to life imprisonment. No death sentences have been passed since.

Sierra Leone is not alone. Fewer and fewer countries execute their citizens and the world has never been closer to a global proscription. When Amnesty launched its global campaign against the death penalty in 1977, only 16 countries had banned the death penalty by law. Today, more than 35 years later, 140 countries have abolished the death penalty either by law or in practice. Last year only 21 countries carried out executions.

The tendency is clear in all parts of the world. Even though the US maintains the use of capital punishment, only nine states executed prisoners last year. This is four states fewer than the year before and this year Maryland became the 18th state to abolish the death penalty. In South America, there are no executions and in Asia Singapore has refrained from carrying out death penalties and the authorities are considering a legislative reform.

Apart from Sierra Leone in Africa, Benin and Ghana have also taken the first steps towards the abolition of the death penalty. In Europe, the last place to gave the death penalty is Belarus.

Proponents of the death penalty point out that it is necessary for the sake of sense of justice, i.e. you seek to meet the desire for revenge of the victim’s family, or you believe that death penalty creates a moral balance after a serious crime. Others believe that the threat of execution has a deterrent effect on criminals, even though no studies document that the use of capital punishment prevents crime. The US states that perform executions do not have fewer murders than those that do not, and in Canada the number of murders has been reduced by half since the abolition of the death penalty in 1975.

More and more government leaders across the world realise that the death penalty is an expensive type of punishment (for instance because of longer legal processes), does not serve as crime prevention, an is a disgrace to society.

The death penalty is the ultimate violation of the right to life, and furthermore often discriminatory, as it is disproportionately used against poor people and minorities.

No matter how good a country’s system of justice is, there is always the risk of convicting an innocent person, and in countries with capital punishment this means the risk of executing innocent people. Unlike other types of punishment, execution excludes the possibility of reversing miscarriages of justice.

Those countries who are in the forefront when it comes to the execution of citizens are often those where the system of justice lacks fairness and transparency, and where human rights are under heavy pressure. China, Saudi Arabia and Iran are obvious examples. The use of capital punishment is often connected to other violations of human right like torture, mistreatment and deeply unfair court cases. Last year on 22 October, the 22-year-old Iranian, Saeed Sedeghi, was executed. Five months earlier he had been sentenced to death for being in possession of a large amount of amphetamine. He never met his assigned lawyer, who had no access to his case before the trial. According to the young man’s family, Sedeghi was tortured in prison and had three teeth knocked out. He told his family that the prison guards had tried to force him to confess in front of a camera but that he had refused. After the execution, his body was send back to the family, but the authorities warned them not to arrange a public funeral.

Along with China, Iraq, Saudi-Arabia, the United States and Yemen, Iran is one of a group of countries that account for the majority of executions worldwide. The fact that the death penalty is no longer used in so many parts of the world is to a great extent due to the fact that countries which claim the right to kill their own citizens have been made to appear as pariahs in the international community.

This has been done through an active foreign policy, in which foreign ministers from the EU, when they meet with other foreign ministers and heads of governments from countries with capital punishment, tenaciously emphasise and criticise problematic issues concerning the use of the death penalty. As a region free of the death penalty (with the exception of Belarus), Europe has assumed an important role as a proponent of the abolition of the death penalty worldwide. Another factor is the UN: successive general assemblies gain more support for a worldwide moratorium, i.e. a global stop to the use of the death penalty. The corporate world has also contributed positively to abolishing the death penalty.

In recent years, the pharmaceutical industry has played a sad part in the implementation of the death penalty, as injections are used as an execution tool in the US and Asia. The use of lethal injections requires the presence and participation of doctors or nurses, and has thereby forced both the pharmaceutical industry and medical associations to take a moral stand on state killings.

In 2011, the Danish pharmaceutical company, Lundbeck, was involuntarily drawn into American death chambers when the authorities in Oklahoma started using the company’s drug Pentobarbitone as one of the main substances in the lethal injection used to execute prisoners. Under pressure, Lundbeck made a change in their distribution procedure that made it possible to block the sale of Pentobarbitone to American prisons applying the death penalty. Furthermore, Lundbeck tried to influence other pharmaceutical companies to follow their example.

Such positive initiatives can ultimately mean that it will become difficult for prison systems to procure the lethal drugs, and may prove effective in reducing the number of executions. Last year, Vietnam had to give up executing prisoners on death row after a futile attempt to import medicine for lethal injections. Tighter sanctions and more companies that refuse to supple medicines, combined with a clear message from the international community, support an overall tendency: support for the death penalty is declining. In recent decades, support in the US has dropped from 80% to 63%, aided by new DNA tests that have shown how an increasing number of innocent prisoners have been convicted. Until a change of attitude has spread to the whole world, the goal must be to isolate those countries that make use of capital punishment. In this way, a global prohibition will one day be a reality.