Equal numbers of boys and girls now start school

In just a few decades, gender equality in schools has increased substantially, thanks to political pressure, school lunches and menstrual cups.

Share

Girl's schooling

Fifteen years ago, 86 girls went to school for every 100 boys, according to the UN. Today, the number has increased to 97 girls for every 100 boys.

The UN World Food Programme now has school food programmes in 63 countries. Since the year 2000, 13 countries have taken over responsibility for their own school food programmes.

In 2013, 48.7 percent of the recipients of the UN school food programme were girls. The same year, the programme reached 19.8 million school children.

More women than men now enter universities in Latin America, the Caribbean, North Africa and large parts of Asia.

Between 1999 and 2010, the proportion of girls who started school increased from 47 to 75 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa. Today, there are 92 girls for every 100 boys in the classrooms of Africa south of Sahara.

MondayMyths

World’s Best News is on a mission. We want to bust some of the most stubborn myths about developing countries that many of us believe in and spread.

For example, only 11 percent of Danes know that nine in ten children in developing regions attend school, and 67 percent do not believe that we are seeing progress in the fight against poverty – even though the proportion of extreme poor has in fact been halved globally.

We risk that such myths hold back world development, and therefore it is important to clear them up.

Other categories

Region: Global

Theme: Children & Youth, Education

While boys go to school, girls are kept at home to do housework and take care of children. Such is the typical idea about the situation of girls in developing countries. And true enough, this scenario has matched reality quite well for many years – however, in most places it no longer remains true.

Only four in ten Danes believe that progress is being made to get equal numbers of boys and girls to start school, according to a survey conducted by Epinion for World’s Best News last year. But the fact is that for the first time in history, we now see just as many girls as boys with a school backpack. And it’s a win-win situation for everybody when girls go to school.

“Women are a huge untapped resource, and it leads to a better society in every way when girls get access to education,” says Anne Poulsen, head of World Food Programme’s Nordic regional office in Copenhagen.

Educated women fight hunger

Studies show that the children of educated women are more than twice as likely to live long enough to celebrate their five-year birthday, compared with the children of mothers without an education. And society as a whole also benefits from giving girls and women the same opportunities as men – among these access to education.

“When girls go to school, they take home skills that make them better at feeding their families and contribute to society. For example, we know that if women in rural areas had access to land, education, and technology to the same extent as men do, then it would mean that we would be able to decrease the number of people who suffer from hunger worldwide by 100-150 million,” says Anne Poulsen.

While true gender equality is still a long way off in most parts of the world, the improved situation for girls in primary school is now slowly beginning to show in other levels of society. For example, the proportion of women in world parliaments has risen to 22 percent from just 14 percent in the year 2000. Several developing countries have even overtaken Denmark when it comes to the number of women in parliament. According to the World Bank, Rwanda currently holds the world record, with 64 percent of parliament seats held by women.

“Education gives women a voice that they can use to participate in democracy. They know their rights, because they are able to read and seek information. Education is decisive,” explains Helle Gudmandsen, Head of Campaign at Danish educational organisation IBIS.

Menstrual cups create miracles

Getting girls to school is not just about changing women’s status in society. Sometimes the simple solutions make the biggest difference. For example, sanitary napkins and tampons are an expensive luxury in developing countries – if they are available at all. Instead, women and girls must make do with anything from cotton and newspaper to bark and mud when they have their menstruation.

These solutions are cumbersome and hazardous to health. The fear of bleeding through keeps girls from attending school for up to 20 percent of the school year – and it can even make them drop out entirely, according to Unicef. That’s why a simple invention such as menstrual cups has an enormous potential to improve girls’ education in developing countries. Danish Ruby Cup has distributed menstrual cups to school girls in countries such as Kenya, Zambia and Uganda. The reusable silicone cup is easy to wash – also in areas where water is a scarce resource – and one single menstrual cup can last up to ten years.

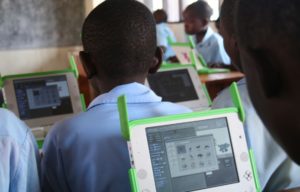

School lunches boost school attendance

Also school lunches mean a lot for children’s education in developing countries. When poor families in developing countries lack food, a school food programme can be enough of a safety net to sustain the family.

“When we introduce school food programmes, we see a distinct increase in the numbers of girls in schools. In places where families are too poor to send their children to school, it is often the girls that they start keeping at home first. That’s why we also sometimes offer an extra monthly ration of food that the girls can bring home to their families, if the children attend school. That gives their families an extra incentive to also give their daughters an education. We have done this with success in several countries, including Haiti and Burkina Faso,” explains Anne Poulsen. According to the UN World Food Programme, providing school meals leads to a marked increase in both enrolment and retention rates for primary school children.

Poverty and childbirth

Even though the girls now generally start primary school just as often as boys, several challenges still remain, regarding girls’ rights. Some countries still go to great lengths to prevent girls from attending school.

“Politics, religion and poverty are still barriers to many girls who want to learn to read and write. That’s why the solution is that we continue the fight against poverty and keep a political pressure to give young people an education,” says Helle Gudmandsen.

In many places, it is a challenge that girls do not advance far in the educational system. Traditions such as child marriages and early pregnancies stop girls from achieving the same as their male classmates. Even the girls who attend school often later find worse and less secure jobs than men – and typically for a lower salary. For example, only one in five paid jobs in North Africa is held by a woman.

“We still see many challenges, but there’s reason to be optimistic about the future. We have come really far, and when people get an education, it impacts nearly every level of society. That’s why we also see that health, economy and the standard of living have increased, as more people get an education,” says Helle Gudmandsen.