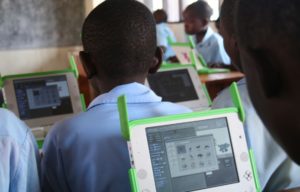

Photo: SocieTrees

Tough trees give food during drought

Villages in western Africa have started to grow a type of tree that survives harsh conditions and can provide nutritious food even during periods of drought.

Share

Parkia: Africa’s superfood

- The tree Parkia biglobosa is a native of western Africa, and therefore a natural part of the ecosystem of Burkina Faso.

- The tree has adapted to thrive in the harsh conditions of the savannah, surviving lack of rain, low soil fertility, and even bushfires, while demanding little in the way of daily care.

- At the same time, parkia roots help retain nutrients and water in the soil, which helps grow other important crops between the trees.

- Parkia fruits are grown for their seeds, which are fermented and pressed into balls called soumbala. These balls are then added to various sauces and dishes for their taste. For this reason, soumbala is often compared to bouillon cubes, but also packs a nutritious punch.

Other categories

Burkina Faso is located close to the Sahara, and often experiences dry spells that make it difficult to grow crops. But in times of need, help is sometimes close at hand; Burkina Faso is also home to the tree Parkia biglobosa, which is a native of the savannah and therefore able to resist very dry and tough conditions.

The tree carries fruits full of seeds that are so nutritious that they can almost replace meat in the diet, thanks to their contents of fats and protein. This has made the small seeds a big ingredient in the local Burkinian cuisine, and even more so during droughts. But even though the women of Burkina Faso have known and harvested Parkia for as long as anyone remembers, there has not been any tradition for growing the trees as a cash crop. Until now.

Growing the future

Recently, a young Danish biologist had an idea. Mette Kronborg is currently finishing her studies of how local communities in west African countries may benefit from growing Parkia trees more efficiently and sustainably. And the 32-year old woman has no intention of letting the results of her project “collect dust on a professor’s bookshelf”, as she says.

Instead, she has founded an organisation called SocieTrees, launching a cooperation with ten villages in Burkina Faso. All told, 100 local Burkinian women have dedicated themselves to plant 50 hectares with seedlings of the hardy trees. The aim is to make the villages more resilient against drought, give the women a chance to earn their own money, and at the same time develop their local communities.

Thanks to support from humanitarian organisations, private sector companies, and private donors in Denmark, SocieTrees was able to plan the first seedlings in Burkina Faso in 2013, and the organisation recently announced that the little trees have taken root and are growing well.

Trees pull money out of thin air

Apart from the physical harvest of Parkia seeds, the tree-planting project also has several other benefits. The dappled shade between the trees is a good place for growing more types of crops on the same plot of land, for example chili peppers and peanuts, that will provide additional food for the local area.

And the trees could also bring in a third, invisible harvest. By CO2-certifying the plantations, the villages will likely be able to sell international emissions allowances. This means that the parkia trees of each village may be able to provide an additional income of around 5.360 euros over the course of 15-20 years.

This extra income would be gained for just keeping the trees standing while they continue to grow and absorb CO2, and in that sense, it’s a bonus income compared to the physical crops. It also gives the villages a source of revenue during the seven years it takes for the trees to mature and start to bear fruit.

The money will go into the village common fund, and 5000 euros goes a long way in the countryside of Burkina Faso. It will be used to investments such as schools and clean drinking water, helping the local area to keep improving itself in the future.

Knowledge takes root locally

SocieTrees is well on its way to achieve the CO2 certifications. The first of two documents has recently been approved by the certification authority PlanVivo, which is also to conduct periodic control visits to the plantations. The process of writing the technical documents has taken longer than strictly necessary, since SocieTrees has insisted on involving the local community.

“The certification authority was a bit puzzled when we insisted on involving the local people in this. But we believe that it is important. After all, it will be the locals that must see this project through to fruition, and therefore it is essential that they also know what it’s all about,” says Mette Kronborg.

When everything is ready, SocieTrees will delegate responsibility for the project to a local organisation of women’s rights in Burkina Faso, but will continue to monitor progress. Mette Kronborg hopes that the project can later be expanded with more trees in the same villages, or expanded to include other local communities in western Africa, the natural home of the parkia tree.